NOTE: This piece is also published in the January 2022 issue of the Pueblo County Historical Society The Lore.

In the early stages of Pueblo’s history, live music entertainment was limited to the Choral Union, Pueblo Cornet Band, or the newly formed city orchestra. On occasion, a “traveling troupe” would pass through on the way to a larger venue. Nationally known musical acts often limited their tours of Colorado to Denver, or Colorado Springs.

In May 1878 the Colorado Daily Chieftain announced a concert by “the greatest musical prodigy living,” the visually-impaired pianist, Blind Tom.

At 29-years-old, Tom Wiggins had already been performing, for almost 20 years. Growing up as a slave, along with his mother and father, he was often hired out by Georgia plantation owner General James Neil Bethune to entertain his antebellum friends. His ability to audibly memorize thousands of pieces of music, and then play them back on a piano, was considered “a wonder.” He was quickly marketed as a P.T. Barnum-style freak, with often cruel advertising of him as a transformation from an animal to an artist. As word quickly spread about his abilities, he would leave the plantation and travel the United States, often performing four shows a day, making about $100,000 a year for General Bethune, who acted as Tom’s co-manager.

By 1873 he had arrived in Denver, for four nights at the Guard Opera House, his first appearances in Colorado. “Blind Tom’s engagement here was a rich treat to all who heard him,” the reviews read.

In Pueblo, the Colorado arrival of what would become one of earliest African American musical superstars would only receive a small newspaper mention. “Blind Tom, the negro musical monstrosity, who has been astonishing large audiences in the principal cities of the United States, is giving entertainments in Denver. The metropolitans are wild with excitement, of course,” the Chieftain noted.

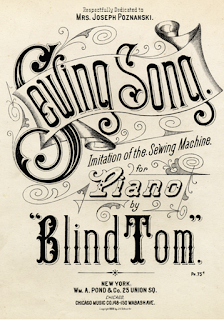

As Wiggins popularity grew, he began writing his own compositions. Sheet music pieces were sold at his shows, as souvenirs for attendees. Titles included “The Battle of Manassas,” “Blind Tom’s March,” and even a novelty piece “Sewing Song,” where the piano imitates a sewing machine. For reasons unknown, later Blind Tom pieces used composer pseudonyms including Professor W.F. Raymond, J.C. Beckel, C.T. Messengale, and Francois Sexalise.

In 1878 he made his way back to Colorado. His tour included Denver, Colorado Springs, various mining towns and finally, Pueblo. The news of his long-overdue local appearance included a more glowing description of his abilities, as compared to the “musical monstrosity” narrative, five years earlier.

May 15, 1878 - Colorado Daily Chieftain

“Mr. Theodore Warhurst, the avant courier for Blind Tom, made us a pleasant call yesterday. This musical prodigy will entertain our people on the night of May 16. He is, undoubtedly, the greatest musical prodigy living.” May 1, 1878 – Colorado Daily Chieftain

His Pueblo concert was considered one of the most anticipated events, that year. The local paper ran daily ads, and promotional stories which bordered on equal parts public relations enthusiasm and side show hype. “Blind Tom, one of the greatest wonders of the age, will visit our town on the 16th. There is hardly anyone in the country unacquainted with this musical prodigy. He is perfectly blind, who has not the mental capacity sufficient to attend to his own wants, and hardly sufficient to understand even a common place conversation, yet he is the perfect master of the piano.” As reported in the May 9, 1878, issue of Colorado Weekly Chieftain.

His sold-out, standing room only concert, at Chilcott’s Hall had patrons standing out in the street, hoping to hear the event. “Quite an audience thronged Santa Fe Avenue and Sixth Street last night, in the vicinity of Chilcott’s Hall, to listen to the playing of Blind Tom. They made some noise, and appeared to appreciate the performance fully, as well as those in the hall.”

But not all of the reviews were supportive of Wiggins’ performance. While classical concert attendees applauded his musical skill, many were confused over the “side show.”

“We had the pleasure of hearing the musical prodigy Blind Tom on Thursday evening. We didn’t fully appreciate the program, as too much time was taken up with Tom’s foolish speeches. Such a musical wonder should not be exhibited for such nonsense. The fault is not in the performer, for he is especially fond of the very highest order of composition, but a general audience likes a popular program, better.”

Little did anyone know about the behind-the-scenes management of his career. General Bethune’s son had taken over bookings of Wiggins, and promoted him as a novelty act, or “a human parrot,” as one critic wrote. When John Bethune died in a train accident, in 1884, his ex-wife Eliza took custody of Wiggins.

Wiggins would return to Colorado, in 1895. He would play Pueblo, one last time on January 18, at the Grand Opera House. Sadly, his visual impairment, odd stage antics, and lack of communication continued to be highlighted, for the sake of ticket sales.

“A helpless idiot, with scarcely sense enough to know when he’s hungry, or to feed himself when he’s hungry, yet endowed with a musical gift far beyond the average musician,” noted a story in the January 15, 1895, Colorado Daily Chieftain.

The concert included a variety of musical selections, including his own compositions. He also included “piano imitations” of various other musical instruments and sound effects, to a receptive audience.

A glowing review of the concert, published by the Chieftain, downplayed any previous behaviors which were deemed a novelty act. “It would be a multiplication of words to attempt to describe the wonderful talent for music this man has. There never has been his equal. In his playing of high-class compositions, he displays his marvelous memory and appreciation of the fine phrasing in them. His playing is perfect.”

In April 1908 Tom Wiggins suffered a major stroke. He died the following June. He was buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn, New York. His story has been the subject of numerous books, documentaries, songs (Elton John’s “The Ballad of Blind Tom”) and artistic murals. The residents of his hometown, Columbus, GA., erected a commemorative tombstone for him, 68 years after his passing.

I have that piano---made in 1864, Steinway and Son---

ReplyDelete